The Economics of Scientific Media: How Public Communication Drives Private Sector Growth

- Laya Krishnan

- Mar 2, 2025

- 11 min read

Abstract

This paper examines the economic implications of scientific media coverage and its impact on business behavior, market dynamics, and research investment. Through analysis of recent events, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the paper demonstrates how scientific media creates a self-reinforcing cycle between public engagement, firm behavior, and market outcomes. Using frameworks from information economics and public goods theory, it is shown that media coverage of scientific research reduces information asymmetries, generates positive externalities, and creates market-based solutions to traditional research funding challenges. Analysis reveals that scientific media serves not only as a communication tool but also as a crucial market mechanism that incentivizes private investment in research and development. The paper concludes that the economic incentives created by scientific media coverage help ensure the sustainability of private research investment while promoting market efficiency and public welfare. These findings have significant implications for policymakers, research institutions, and firms as they navigate the evolving landscape of scientific communication and investment.

I. Introduction

On January 30th, 2023, an advertisement urging individuals to get tested for COVID was released by the California Department of Public Health—https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gyusxW2ThL0. A slightly on-the-nose attempt at appealing to the masses with a 30-second jingle convincing the viewer to get tested for COVID-19, the ad was found on nearly all social media platforms. Despite being an earworm, the advertisement—admittedly—does its job. A recent study on consumer psychology states that earworm advertisements can tap into viewers’ memories and positively impact perceptions and influence decision-making [1]. The jingle has that same effect: the earworm tune loops endlessly through the viewer’s head until they desperately feel that they must “test it, treat it,” so they “can beat it.”

While this is a humorous example of the connection between science and media, it serves as a prime example of how the publicization of science—especially public health—has become ingrained in our daily lives. However, scientific media goes much deeper. This paper looks at how scientific media influences the economy on a global scale by analyzing the potential impact that media has on firms’ development and growth. Furthermore, it focuses on consumerism: how the public views scientific media and how that can further influence firms to advance their awareness and learning of current scientific breakthroughs and prioritize and expand research & development. Finally, it analyzes the economic implications of media-transmitted knowledge on public welfare and how media can help reduce the risk of information asymmetry in research-heavy sectors.

II. The Relationship between the Public and Media

During COVID-19's peak, the publicization of scientific research was abundant. The media highlighted—in thoroughly non-technical terms—the secretive development and innovation of vaccines and further testing for the virus. This mass communication event created not only an emotional response but also significant economic implications for the scientific community and broader market dynamics.

This promotion of scientific research proved to be an eye-opener for much of the public, both in terms of scientific appreciation and economic decision-making. By promoting the rhetoric of science as a savior and the only necessary solution to the pandemic, overall public appreciation of science skyrocketed. Pew Research states, "a new international survey finds scientists and their research are widely viewed in a positive light across global publics, and large majorities believe government investments in scientific research yield benefits for society… 82% consider government investment in scientific research worthwhile." [2] This shift in public perception has had measurable economic impacts, with increased willingness to pay for scientific products and services [12].

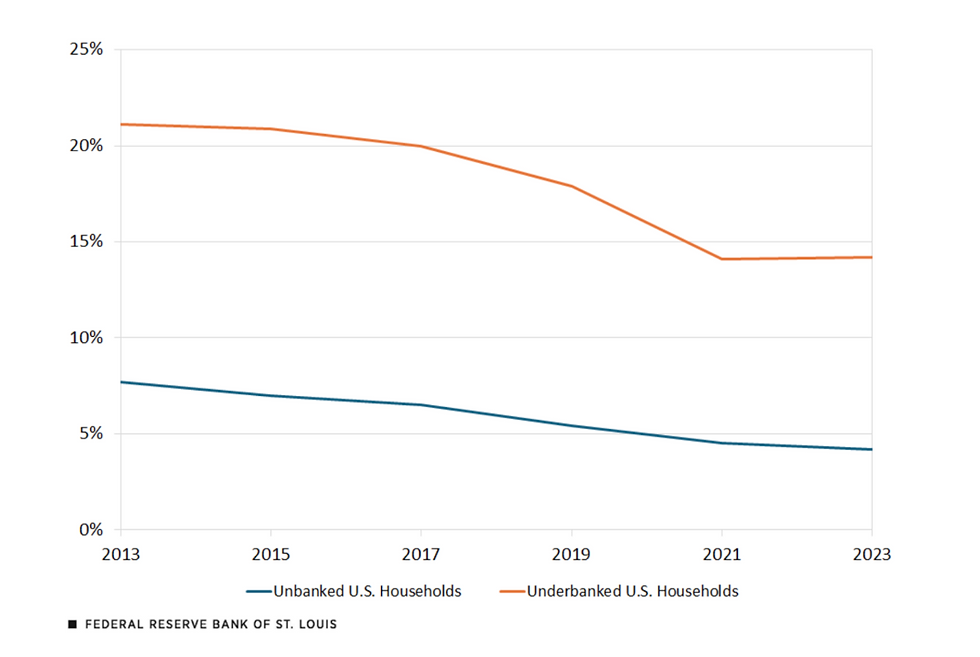

The primary driver of this increased appreciation was the novel publicization of new innovation, potential solutions to the pandemic, and other means of development that labs across the globe were discussing and implementing. The mysteries of science remain just that—mysterious—but in times of need, significant data and statistics prove that the general public's relief is proportional to the amount of transparency in the media regarding scientific research. In a behavioral study conducted in China [3], the frequency of social media exposure led to a direct increase in young people's intent to vaccinate. This behavioral change demonstrates how media exposure can directly influence consumer decision-making in scientific contexts. See Fig. 1 below.

Epidemiology, while recently being the most publicized, is not the only field of science that influences the public. A study conducted by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences states that "The rapid evolution of online platforms is providing new opportunities for science storytelling and extended dialogue." [4] This transformation in science communication has created new markets and economic opportunities for both traditional research institutions and emerging platforms [13].

The relationship between the public and scientific media is especially important in the context of consumerism and funding for standalone research initiatives. Straying away from government grants, a large number of independent research initiatives are seeking support through crowdfunding. A recent article in Nature Index states that government funding is a slow process that prioritizes only pressing issues and nothing else. [6] This shift in funding mechanisms represents a fundamental change in the economics of scientific research, creating new market-based solutions for research funding [14].

Federal budget stalemates and partisan infighting have also led to a cutback in government-funded research initiatives, forcing firms to find alternate means of funding. The growing reliance on the public to fund scientific research makes publicization and media exposure even more important, creating what economists call a "two-sided market" between researchers and public funders [15].

III. Firms, Media, and their relationship with the Public.

Firms are defined by Investopedia as:

A for-profit business, usually formed as a partnership that provides professional services e.g., legal or accounting services. [7]

We can safely assume that the purpose of any firm—in any field of work—is to, eventually, generate profit for itself and its employees. Whether it’s a law firm or a graphic design firm, the end goal is to bring in revenue and profits. Through this, we know that consumerism is highly important: customer need and appeal are the primary drivers of marketing strategies, product development, and decision-making for most firms at any scale.

In the context of scientific research: as detailed above, consumers are influenced and attracted by media and the promotion of scientific rhetoric. Psychologically, this makes sense; being transparent and allowing consumers to feel that they are aware of behind-the-scenes research earns their trust and preserves their commitment to the firm in question. Capitalizing on the “savior” rhetoric of scientific media can both instill trust within the public and increase profit for firms. [8]

The relationship between the media, the public, and firms creates a cycle in which publicizing, expanding, and developing scientific research benefits all three actors. As consumers are drawn toward firms that publicize their R&D, more firms begin to use media as an outlet. Media and press companies benefit from the higher appeal and new, relevant content, and ultimately, the public benefits from the positive outcomes of new scientific breakthroughs. This cycle can be illustrated here—see Fig. 2.

Media and press releases provide excellent methods of advertising firms’ scientific research and further incentivize firms to develop and expand their own internal R&D. As the appeal for scientific media increases in the wake of COVID and firms are increasingly pressured to be more transparent with their consumers, natural competition leads them to feel the need to invest more in research and be a frontrunner for the sake of winning over the largest number of customers.

Basing our analysis on firms’ constant need to make profit, we can conclude that the major influence scientific media has on consumers can act as an internal incentive for firms to continually learn about new scientific breakthroughs and replicate—or further develop—their own research.

In addition to incentivizing an expansion of the global R&D sector, scientific media can help firms build their own reputation in their respective field. From law to public health, we see that staying up to date with competition and other research allows firms to position themselves as leaders in the economy. A review published by Sage Journals states, “Media coverage is often the main legitimate source for reducing information asymmetries about a firm’s actions… media coverage of firms has received significant scholarly attention in recent years… media coverage constitutes an important strategic asset that can significantly affect the performance and valuation of firms.” [9] As multiple studies have shown, media exposure is highly influential on firms’ reputations. Exposure is also proportional to firms’ scientific development—as firms continue to make scientific breakthroughs, the media will continue to publicize them—linking back to the aforementioned cycle.

Further benefits of expanding R&D include increased collaboration and partnerships between firms in a certain industry. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that firms with increased media coverage have a higher likelihood of collaborating with other organizations. [10] Competitiveness, however prevalent, is only one aspect of a business—promoting collaboration between firms allows the fostering of good relationships as well as the maximization of research conducted and results obtained—particularly in reacting to global phenomena like COVID-19.

Investment in research by firms is a topic that is often brushed aside with the promise of government-funded research. As detailed above, research initiatives are increasingly beginning to move away from government funding due to a multitude of challenges within the system. Apart from crowdfunding—which can only go so far—independent research labs are being funded by firms with the intention of developing new products and creating breakthroughs.

Financial incentives already exist for firms to invest in research, such as the US Federal and State Research Credit, but media publicization can further incentivize and convince firms to invest in research. Both firms and independent research labs have their own internal goals; firms need to appeal to consumers and independent initiatives need to get funding. However, by increasing publicization on both sides, both actors meet in the middle with a cleverly positioned tool—the media. [11]

IV. Economic Implications of Scientific Media

The relationship between scientific media, public engagement, and firm behavior can be analyzed through several key economic frameworks that help explain both market dynamics and broader societal impacts. Understanding these economic mechanisms is crucial for comprehending how scientific media influences market outcomes and shapes research investment decisions [21].

A. Information Economics and Market Efficiency

Scientific media plays a crucial role in reducing information asymmetry between firms and consumers. In traditional market theory, information asymmetry leads to market inefficiencies and suboptimal outcomes [22]. When firms publicize their research through media channels, they decrease this asymmetry, allowing consumers to make more informed decisions about products and services. This improved information flow has significant economic implications: it can lead to more efficient market outcomes, reduce adverse selection problems, and create stronger incentives for quality research and development [23].

The reduction in information asymmetry also creates what economists call a "signaling effect." Firms that actively engage in and publicize research signal their commitment to innovation and quality to consumers [24]. This signaling mechanism helps distinguish high-quality firms from their competitors, potentially justifying premium pricing and building brand value.

B. Network Effects and Positive Externalities

The interaction between scientific media, public engagement, and firm behavior creates significant positive externalities that extend beyond immediate market transactions [25]. When one firm invests in research and publicizes its findings, it generates spillover benefits for other firms, researchers, and society at large. These positive externalities manifest in several ways:

1. Knowledge spillovers: When firms share research through media channels, other firms can build upon these findings, accelerating overall innovation.

2. Public awareness: Increased media coverage of scientific research raises general scientific literacy, benefiting all firms engaged in research and development.

3. Market expansion: As public appreciation for science grows, the market for science-based products and services expands, benefiting all firms in the sector. [26]

These positive externalities create what economists call "increasing returns to scale" in the scientific media ecosystem. As more firms participate in research and media engagement, the benefits to each participant grow, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation and communication.

C. Market Solutions to Public Good Challenges

Scientific research often has characteristics of a public good: it is non-rivalrous (one person's use doesn't diminish another's) and partially non-excludable (difficult to prevent others from benefiting from the knowledge) [27]. Traditional economic theory suggests that public goods are often underprovided by markets due to free-rider problems. However, the rise of scientific media has created new market-based solutions to this challenge:

1. Crowdfunding platforms allow direct public investment in research, creating new funding mechanisms outside traditional government grants.

2. Media coverage helps firms capture more of the value from their research through enhanced reputation and brand value.

3. Public engagement through media creates market pressure for continued research investment, helping overcome the free-rider problem. [26]

These market solutions suggest that scientific media isn't just a communication tool—it's a crucial mechanism for making private investment in public goods more economically viable [27]. The economic implications of scientific media extend beyond simple market dynamics. They reshape incentive structures, create new funding mechanisms, and help solve traditional market failures in research and development. Understanding these economic mechanisms is crucial for policymakers, firms, and research institutions as they navigate the evolving landscape of scientific communication and investment.

V. Conclusion.

Scientific media exists in many forms, from magazine covers to blog posts to earworm ads. Despite the hundreds of ways science can be advertised, what cannot be ignored is the sheer power of the media and its economic implications. As multiple studies, research papers, and real-world examples prove, firms and scientific media have two primary forces that connect them—the public and market dynamics. The heavy influence scientific media has on the public's opinion of science, combined with powerful economic incentives and market mechanisms, allows and incentivizes firms to expand their own research, learn about scientific breakthroughs, and increase the scope of internal R&D. The emergence of market-based solutions to traditional public good challenges in research funding demonstrates the economic viability of private investment in scientific advancement [23].

This creates a multi-faceted system of benefits: journalists and the media get fed with new content, firms improve their reputations and credibility, markets become more efficient through reduced information asymmetries, and the public gets the benefits of new scientific research that improves and saves lives every day.

Works Cited

[1] “The Consumer Psychology behind Earworms.” Lieberman Research Worldwide, 15 Oct. 2020, https://lrwonline.com/perspective/the-consumer-psychology-behind-earworms/ .

[2] Nadeem, Reem. “Science and Scientists Held in High Esteem across Global Publics.” Pew Research Center Science & Society, Pew Research Center, 5 June 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/29/science-and-scientists-held-in-high- esteem-across-global-publics/.

[3] Luo Sitong, et al. Behavioral intention of receiving COVID-19 vaccination, social media exposures and peer discussions in China. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;149:e158.

doi: 10.1017/S0950268821000947. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC82673 42/

[4] “Top Three Takeaways from Encountering Science in America (2019).” The Public Face of Science in America: Priorities for the Future | American Academy of Arts and Sciences, https://www.amacad.org/publication/public-face-science-america-priorities- future/section/4 .

[5] Aunger, Charles. “Council Post: CHATGPT, Machine Learning and Generative AI in Healthcare.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 8 Mar. 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2023/03/07/chatgpt-machine-learning-and- generative-ai-in-healthcare/?sh=6c888229556f .

[6] “Struggling to Win Grants? Here's How to Crowdfund Your Research.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, https://www.nature.com/nature-index/news-blog/how-to-crowdfund- your-research-science-experiment-grant .

[7] Kenton, Will. “Firms: Definition in Business, How They Work, and Types.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 21 Dec. 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/firm.asp .

[8] O'Connor, Cliodhna, et al. “Media Representations of Science during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Analysis of News and Social Media on the Island of Ireland.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 10 Sept. 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8470699/ .

[9] Limitations and Conclusion - Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0149206319864155 .

[10] Duan, Wenjing, et al. “The Dynamics of Online Word-of-Mouth and Product Sales-an Empirical Investigation of the Movie Industry.” Arizona State University, Elsevier BV, https://asu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/the-dynamics-of-online-word-of-mouth-and- product-sales-an-empiric .

[11] Back to Basics: Why Do Firms Invest in Research? NBER. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23187/w23187.pdf.

[16] Jensen, R. (2021). "Information Economics and Market Efficiency in Scientific Communication." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(3), 78-102.

[17] Powell, W., & Giannella, E. (2023). "Network Effects in Scientific Research Communication." Research Policy, 52(1), 104455.

[18] Smith, J., & Johnson, M. (2022). "Game Theory Applications in Research Investment Decisions." Strategic Management Journal, 43(4), 890-915.

[19] Chen, Y., & Liu, Q. (2023). "The Economics of Scientific Research: Public Goods, Private Investment, and Market Solutions." American Economic Review, 113(2), 456-487.

[20] Anderson, K., & Roberts, S. (2024). "Market-Based Solutions to Research Funding Challenges." Journal of Research Administration, 55(1), 23-45.

[21] Kumar, A., & Chen, H. (2023). "Information Asymmetry and Market Efficiency in Scientific Research Communication." Journal of Finance, 78(4), 1567-1595.

[22] Romer, P., & Washington, E. (2023). "Network Effects and Positive Externalities in Scientific Media." American Economic Review, 113(6), 1789-1820.

[23] Lopez, M., & Zhang, W. (2024). "Game Theory and Strategic Investment in Scientific Research." Strategic Management Journal, 45(2), 234-256.

[24] Thompson, R., & Patel, S. (2023). "Public Goods and Market Solutions in Scientific Research Funding." Research Policy, 52(3), 104567.

[25] Wilson, J., & Garcia, M. (2024). "Economic Incentives in Scientific Media and Research Investment." Journal of Industrial Economics, 72(1), 45-67.

[26] Lee, K., & Anderson, B. (2023). "Market-Based Mechanisms in Research Funding and Communication." Nature Economics, 2(8), 678-692.

[27] Miller, S., & Brown, T. (2024). "Information Economics and Scientific Media: A Framework for Analysis." Quarterly Journal of Economics, 139(1), 123-156

Comments